What’s a standardized patient?

As an actor, I had no idea there was this world of incredible possibility where I could both utilize and scratch my acting and teaching itches simultaneously.

Enter the role of the standardized patient.

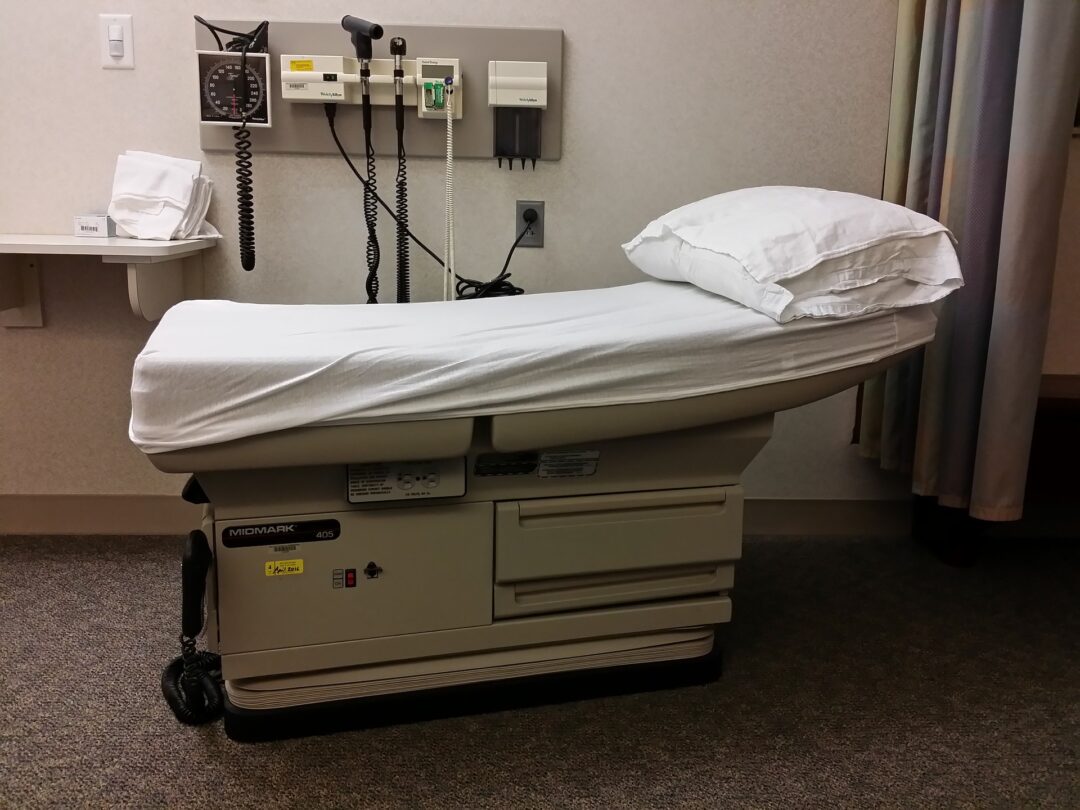

A standardized patient, or SP, is an actor who works with medical, nursing, physician assistant, and dental students to give them opportunities to (put lovingly) screw up with me so they don’t screw up with a patient.

I’ve also worked with other programs such as vet schools, where I play a client/parent of said animal, and with CHP and detectives as a victim or suspect.

For the purposes of this post, I’ll focus on medical students just fyi.

It provides a safe space for students to stretch their info gathering skills, create and build rapport, sus out their differential (different things they believe could be going on with you) real-time, and bottom line, get those nerves out.

My role is this: retain important info of the patient and embody them while also providing appropriate improv skills to then give the student the best ‘real life’ learning environment possible through what we call encounters.

This kind of work has not only been incredibly rewarding but often can be a challenge too, in the best way possible.

Sometimes my best performances are to an audience of one. Well, not really an audience. It’s more like an unwilling scene partner 😉

I’ve learned more things than I can count, not just about acting, by doing this job, but here’s the three that really stand out to me.

(Seriously, side note, for the recovering slight hypochondriac that I am, my medical knowledge has skyrocketed, and my white coat syndrome has improved in ways I couldn’t have imagined. So, grateful from many directions. Alright, moving on, I just had to gush about that.)

Living in improv’d world

Improv.

I feel like actors really only have two responses when improv/improvisation is brought up. Either it’s loved or loathed.

I was one of the loathed category for a very, very long time.

To be fair, I love watching improv. However, the great deal of improv that I had experience with was the classic party games, and ‘you’re on a beach-go!’ Basically, like scenarios on Whos Line is it Anyway?

Not my cup of tea as an actor though.

Being a standardized patient turned this hate of improv to absolutely loving it because it was rooted in truth. There was a structure around it, it was grounded, and I had a template to work with.

So, let’s say the case I’m working on is that of a young woman coming into the clinic with abdominal pain. The script would have important info such as my age, occupation, past medical history, social history, and current symptoms.

Most scripts will have what they call a chief complaint or opening line, such as, “My stomach has been really bothering me for the last few days.” And perhaps some other peppered lines scripted throughout.

Then you have the important info to remember, but otherwise, there’s a lot of off-the-cuff improv and, well, how the world communicates, unplanned and unscripted conversations, right?

So while I have important info to memorize, such as past medical history, the student may ask about my hobbies. Or my spouses’ name, where I went to school, the possibilities really are endless.

If those answers aren’t in the script, its up to me to provide a realistic response.

It’s just enough improv to stretch those muscles and gain confidence in doing improv. (Again, not the Whos Line kind of improv, but the kind of improv that is incredibly helpful when performing.)

Seriously, this work has massively upped my improv game.

Being a standardized patient means accurately displaying pain.

I’d say unless you’re doing a melodrama or a German expressionist piece, accurately displaying pain is a key component to acting.

Characters a great deal of time are in some kind of physical pain. Being an SP helps hone that piece of your craft in an authentic way.

So, each script will have something called a pain scale.

The default question from the student usually goes like this…

“Okay, so, on a scale of one to ten, one being no pain at all and ten being the worst pain you can imagine, where does this pain land?”

Say my pain is at a 7 so my response would be, “I dunno, probably about a 7.”

Then encounter would continue.

7, that’s pretty painful right?

Now, pain scale is usually where movement work enters.

I had to highlight movement, right, that’s what I’m all about after all 🙂

For this hypothetical case then, with abdominal pain that’s pretty intense, is where I bring in my friend Rudolf Laban.

The movement notation he created works incredibly well for this kind of work and any role for any medium where pain is present.

Using qualities such as wring, slash, heavy and bound are elements of Labanotation that I utilize quite a lot.

It’s kind of a win-win for me and the student. They get to hone their craft while I hone mine.

Listening…lots of listening

Listening.

It’s kind of key for actors.

Well, all humans, but that’s a slightly different conversation.

For a lot of acting teachers, listening is a cornerstone of the craft.

As in real life, it can be pretty easy to tell when someone isn’t listening.

It doesn’t feel good when you’re on the receiving end of that.

And if you’re in the middle of a performance, you can feel neglected by your scene partner.

Staying in the SP encounter, and being in the moment, requires careful listening.

And it’s wonderful to witness too because this is something that the students are learning as well.

Doing encounters like this get’s them out of their heads, and if they start asking the same questions a few times, they’re going to see real-time a patient that gets annoyed they’re not listening.

A reminder in self-awareness

One last piece I wanted to mention that I love about this work is homing in on language.

People are curious creatures. I keep finding some things that people do unconsciously to be just incredibly fascinating.

Another reason this creates a safe space for the students is for when they are learning how to approach difficult topics.

How to deliver bad news, ask about sexual history or how to navigate a difficult patient.

It’s always a wonderful reminder in the importance of self-awareness when I have a student do this:

Student: “What about your family medical history? Anything run in the family?”

Patient: “Well, yeah, my mom died of breast cancer two years ago.”

Student: (Writing down notes) “Good, good.”

I can guarantee the student did not say “Good” because my mother died of cancer. Rather, it was an unconscious verbal pat on the back. The student saying to themselves, “Good, good, I asked that question and got an answer, I’m doing great!”

Standardized patient work is kinda wonderful.

Not kinda, really. It’s really wonderful.

I’m not sure where I would be as an actor without becoming a standardized patient. I don’t want to ponder it, really, as I know, it’s only helped strengthen my craft in ways I hadn’t anticipated.

And hey, some of my best performances have been to that one unwilling scene partner, and that makes my teacher side really, really happy.

It’s a way of using my craft to give back to the community in a very practical way.

Interested in doing standardized patient work?

If you’re intrigued, I’d recommend checking out the medical schools near you and see if they have an SP program.

As mentioned before, other schools such as nursing, vet, dentist, CHP development, and continuing education programs also hire actors to help flesh out the learning process.

I really encourage you to check it out! Guarantee you’ll learn some fascinating stuff!

Did I mention it’s acting work you get paid for? 🙂